Blockchain, a slow disruption for the film industry

By Antonio Peláez Barceló

Canadian movie financing expert Manuel Badel had a vision in 2018 where financing projects could become more transparent, faster and traceable.

Badel believed then that blockchain, the technology behind the use of digital currency, could revolutionize how film and television industries work.

He continues to say it.

“It’s a slow disruption,” Badel told Humber News.

Traditionally, films have been funded in part by presages, agreements between the producer and distributors from different countries.

Badel said that usually this was a barrier for independent producers.

URJC Madrid University movie marketing professor Rafael Linares agreed and said this used to be a slow process in which producers and distributors often lacked information about each other.

With a contract backed by blockchain, this could change. “You may have all the information in real time,” Linares said.

Photo: Manuel Díez / URJC

In 2019, Badel wrote a report commissioned by Telefilm Canada in which he showed examples of how blockchain had already been used and how Canadian movie firms thought it could be used.

“The whole system, the whole value chain wins out,” Badel said of a technology first used by bitcoin.

Ann Brody, a communications PhD student at McGill University, told Humber News that before bitcoin and blockchain appeared digital currencies hadn’t solved the double spending problem.

This problem was like counterfeit money and arose because these currencies were designed without a trusted central authority.

The Bank of Canada is the only issuer of legal currency in Canada. When a $10 bill is spent by a person, the Bank of Canada guarantees that bill is unique and could be used to pay for a ticket to a movie.

But without a central authority, everybody could copy that bill.

With electronic money, until the appearance of bitcoin, anybody could claim they still had $10 for a movie ticket.

Bitcoin introduced an automatic ledger where all the transactions were recorded in a chain of blocks and couldn’t be erased or changed.

It was like the central authority but without any human behind controlling it.

Bitcoin, blockchain and movies

“It started with the 2008 financial crisis, so bitcoin was like a response to that financial crisis,” Brody said.

That year, a person or people using the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto developed the concept of cryptocurrency and introduced it in a white paper titled Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System.

In Nakamoto’s paper, the main features of bitcoin were security, decentralization and traceability.

Security was based on a system of public and private keys, which date back to the 1960s, according to The Book of Crypto, written by adjunct professor Henri Arslanian at the University of Hong Kong.

Working for the security and integrity of the system was rewarded with bitcoins in a process called mining. But if the miners failed or tried to hack it, they were penalized.

The integrity and traceability of the system were guaranteed by a chain of blocks, where the transactions were stored. All transactions were traceable as they couldn’t be erased or modified.

In the beginning, nothing could be purchased with bitcoin, but on May 22, 2010, a programmer who lived in Florida decided to buy two pizzas. [Link to the whole original online talk]

He paid 10,000 bitcoins (BTC) to a member of the bitcoin community who went to buy the pizzas, priced at US$25.

In 2023, those 10,000 bitcoins could be around US$290 million, the official budget for Mission Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part 1.

Smart contracts, a powerful tool for movies

Bitcoin could buy pizza. And if movie theatres allowed it, it could pay for a ticket and the popcorn.

But it could not produce, distribute, exhibit, or even collect the movie ticket.

Russian-born Canadian Vitalik Buterin, was 18 years old in January 2014 when he wrote the white paper for ethereum.

“Vitalik Buterin wanted to expand the usability of bitcoin,” Brody said. “He saw it was limited to the monetary realm.”

Brody said Buterin added to blockchain the ability to record code and not just monetary transactions.

Buterin’s paper was titled A Next Generation Smart Contract & Decentralized Application Platform.

The paper outlined a new system that could handle decentralized operations thanks to what it called “smart contracts.”

A smart contract “is a program with pre-coded rules and conditions into it that when are met, the program executes it,” Brody said. “It’s like a contract, a regular contract in the non-digital world.”

But while in the non-digital world, a lawyer or a notary is often needed to certify it, with ethereum this happened automatically in the blockchain.

It opened possibilities not only for programmers or gamers, but for musicians, writers and, of course, producers and filmmakers.

First experiences with media and blockchain

Cryptocurrencies, according to The Book of Crypto, had the advantages of being global, always available, cryptographically secure, fast and inexpensive.

But the book warned they were highly volatile.

That was one of the reasons why Rafael Linares says blockchain was not the solution to financing problems.

“But I believe it provides a key solution to the industry in terms of speed, reliability between the parties and credibility,” Linares said.

Manuel Badel disagreed and said it could be used for financing.

Badel said he discovered blockchain when he attended the South by Southwest (SXSW) conference and festival in Austin, Texas, in March 2016. A presentation about blockchain and film called his attention.

“I had heard about bitcoin, but I didn’t know what blockchain was,” Badel said.

He said the presentation showed a software application for screenwriters based on blockchain which allowed contributions to be traced and eased the payment of royalties.

After that presentation, Badel said he attended a congress in Toronto with around 300 people about blockchain where “I think I was the only person who worked in the film or TV industry.”

He said he learned more about it and started to work on applications for the media.

Badel said he then proposed to francophone Ontario television (TFO) to create a smart contract to manage a TV collection.

“All the relations between the various stakeholders, the producer, the creative people, the broadcaster, the financiers, the distributor were linked by a smart contract,” he said.

It was Canada’s first project in the broadcast industry, Badel said.

Following the success of that project, Badel said Telefilm Canada approached him about writing a report in 2018 on the Canadian audiovisual industry and blockchain.

While he was writing that report, which would lead him to interview more than 80 people, Telefilm Canada contacted him again. Canada was the guest country in the European Film Market (EFM) at the Berlin Film Festival and Telefilm Canada wanted to show Canada was an innovative country, Badel said.

In February 2018, Badel organized a three-hour conference that included a hands-on workshop at the Berlin festival market.

Several film scholars have mentioned the role of the film markets during film festivals as gathering places for movie industry professionals. Including Cindy Hing-Yuk Wong in her book Film Festivals, where she wrote specifically about Berlin and Cannes markets.

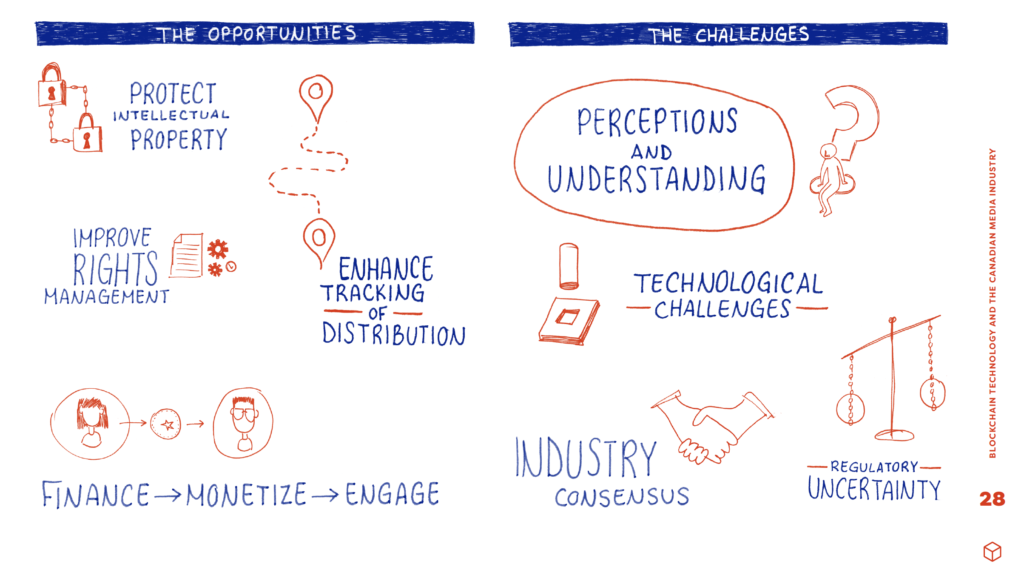

As for the study for Telefilm Canada, published in 2019, Badel said its conclusions would be valid currently, even though some examples would be outdated.

Several companies mentioned on it have not survived, such as Veredictum or Breaker Studios. And the same happened with movies such as Atari, which was even announced to star Leonardo di Caprio.

However, other companies such as Vevue or films like Braid did work. And even new firms like Blockfilm or NFT based Mogul Productions surged in 2021.

But apart from those initiatives, Badel said for Humber News one of the main advantages of bitcoin in general is traceability.

“For private investors, it’s interesting,” Badel said. “Because if you can prove the film is sold and the revenues are going to be clearly identifiable, they are going to invest in the film.”

Besides, the report said that the public could support an artist or a cause, and their role could go “well beyond that of simple spectator.”

It also said that the difficulty of the underlying concepts, the regulatory aspects and the role of decentralization were obstacles for this technology.

Nowadays he said, “we have to work with banks, with organizations, and that all takes time.”

But he said he has also developed a platform.

“Currently it’s only a prototype, but I have created Platz with the final idea of stimulating private investment,” he said. “Although, at this moment, there are regulatory and legal conditions that are not going to stimulate it.”

Somehow, Badel was anticipating what the two companies that will be discussed next would do. Although one of them, as happened with the firms from the report ceased operations. And the other didn’t.

A Russian distribution platform that failed

In May 2018, Movieschain’s Chief Content Officer Elena Khlebnikova presented a blockchain platform at the Next section of the Cannes film market.

She said that the mother company Tvzvar had created Movieschain to showcase Russian cinema worldwide.

“We have our own tokens and our own content distribution network, which can be accessed all around the world,” Khlebnikova said.

Photo: Antonio Peláez Barceló.

She said the tokens were only used for the platform.

“When the owner of the film rights comes to the platform, he fixes the money in euros and the platform converts them to tokens,” she said. “It’s the same when the user pays for the content, they do it in their local currency and the platform does the conversion.”

Khlebnikova said there was no currency risk.

Movieschain, in the end, offered a video-on-demand system for Russian cinema available worldwide under blockchain technology.

Of the six companies that attended the Next section of the Cannes market that year, only Germany’s Cinemarket has continued working.

Two were in beta or alpha status (according to their websites), and a total of three shut down, including Movieschain. Its mother company Tvzvar kept on working in Russia.

Lumiere, a startup based on a doctoral thesis

The expert in movie financing Patrice Poujol was finishing his doctoral thesis by then but also attended the 2018 Cannes Film Market.

Shortly before the 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent arrival of bitcoin, Poujol had completed a master’s degree in film production while taking a sabbatical from his job at a French bank.

“And then the 2008 crisis happened, and my boss was like, Come back, otherwise you lose your job,” Poujol said.

Poujol said he never went back, but instead had a PhD in Creative Media from the City University of Hong Kong and founded Lumiere, a finance solutions firm for entertainment.

Springer publishing house released in 2019 his book Online Film Production in China Using Blockchain and Smart Contracts, which was based on his PhD dissertation.

After presenting case studies and analyzing the situation in urban China, Hong Kong, Europe and the U.S., a chapter of the book included the proposal for his own company.

“We started with a system that would enable transparency fundraising and fan engagement at a much stronger level than Kickstarter,” Poujol said.

One of his first clients was the film Papicha, directed by Mounia Meddour, which was presented in the Un Certain Regard section of the Cannes Film Festival in 2019.

It received numerous awards at other film festivals and two Cesar Awards, which are France’s Oscars.

In 2022, Poujol had another project, a documentary about the Japanese designer Kenzo Takada.

Before presenting it at Cannes, Lumiere put up a building in the Decentraland metaverse, in which his life and work could be seen.

They included eight non-fungible tokens (NFTs) in that virtual building.

According to The Book of Crypto, by Hong Kong Professor Hernri Arslanian NFTs are “tokens that are unique, using the properties of blockchain technology.”

Although the technology was previously available, they became popular on March 11, 2021, when Christie sold artist Beeple’s digital collage titled The First 5000 Days for US$69 million.

Badel’s report on blockchain already talked about their precursor, Cryptokitties, “a game developed in Canada that allows players to collect and trade for virtual cats.”

Before the release of the movie Barbie, Mattel sold several varieties of Barbie NFTs and after its success their number has increased in NFT markets like Mint or Flow.

But Poujol, Badel and Linares think that NFTs would go beyond selling works of art.

Poujol said he wanted to revive the idea of the gift. He said he would add to an NFT an additional experience to the cinema ticket, including visits to the set or dubbing one of the characters of an animated film.

Linares said that when he was a child, he used to keep and collect movie tickets. With NFTs, he said more features can be added to that ticket.

“And [director] Kevin Smith has invented a system in which his last movie is an NFT,” Linares said. “You don’t need a distributor to sell copies, you sell that NFT to one person, you get the money and that person will distribute it or sell it.”

Badel agreed and said NFT could serve as proof of ownership or certificate.

The uncertain future

As it’s been said previously, bitcoin has already been used in the movie industry.

Although blockchain started as a decentralized initiative, it has been used both by art-house films and big studios.

Regarding its future, Ann Brody said she wouldn’t consider herself a libertarian, but she didn’t like how wealth was concentrating “in the hands of a few and governments, and corporations.”

“Reclaiming your autonomy and power is something that people need now more than ever”, she said. “Gaining the right values into this ecosystem is very important for the future and success of cryptocurrencies and blockchain.”

Linares, who has also produced independent films, said he thought smart contracts would be important in the future. But in terms of marketing the majors would take advantage of NFTs.

“This also has a lot to do with AI,” he said. “Imagine when my daughter realizes she can watch a movie about multiverses being Spiderman and changing the character or changing your face in Mission Impossible.”

In a different direction to Linares’ imagination, Poujol underlined the empathy that films provide and how he still remembered the first film he saw in a theatre, Once Upon a Time in the West.

“If this works, I would like to eat my own medicine,” he said. “I would leave the company because there’s one film I want to do before I die.”

Finally, Badel said he envisioned a film industry collaborating, perhaps in line with what Brody said about the ideals of decentralization.

“We have to talk about contracts management, certificates, traceability,” he said.

“All this is going to lead to an industry that’s going to be more efficient by collaborating,” Badel said.“And finally, it will free more money for public institutions, so they’ll be able to fund more contents.”